A short history of the island

Throughout the 19th century, ship traffic in the Gulf of St. Lawrence intensified considerably. Some 2,000 people inhabited the Mingan region during this time. They earned their livelihood by fishing for seafood – cod primarily. An impressive fleet of schooners worked the coast between Natashquan and Mingan. As settlements became permanent, supply and passenger ships began providing regular service.

Between 1857 and 1885, five major shipwrecks occurred in the Mingan Islands area, thus creating additional pressure to build a lighthouse on Île aux Perroquets. At that point, ocean and river transport companies joined forces with coastal fishermen to demand that the government establish navigational support services.

As early as 1877, the town council of Pointe-aux-Esquimaux — now known as Havre-Saint-Pierre — petitioned to have lighthouses built on Walrus Island — now known as Petite Île au Marteau — and Île aux Perroquets. With the support of letters from the Allan Company in 1885 and Commander William Wakeham in 1886, the shipowners’ requests were finally accepted. The Île aux Perroquets lighthouse station was erected in 1888, with Henry de Puyjalon serving as its first keeper.

The Île aux Perroquets Lighthouse

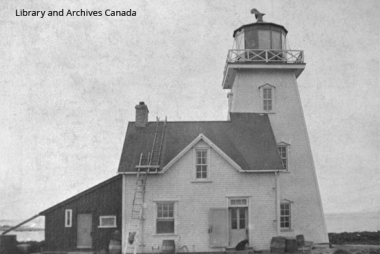

Erected in 1888, the Île aux Perroquets light was a wood building abutting the home of the lighthouse keeper’s family, the assistant keeper and the other staff members whose services were required to operate the lighthouse properly.

The lamp was essential for guiding ships, obviously, but other means of communication were also needed to establish or maintain contact with navigators, including flags, sound signals, a telegraph system, radio beacon and telephones.

A flagstaff made its appearance at the Île aux Perroquets lighthouse station very early on. Beginning a half century prior to that time, a system was implemented throughout the marine sector that employed flags and pennants in a variety of colours, with each flag representing a particular letter or number. This ingenious procedure, operated according to the International Code of Signals, used 18 different flags to compose 78,000 different signals as well as the name and number of more than 50,000 ships.

Ships passing offshore were thus able to receive messages from the light keeper on duty. Alternately, messages could be conveyed to the keeper, who then relayed them to telegraph stations on the mainland. This information was then, in turn, transmitted from one station to the next until reaching Québec City. Shipping companies were thus able to track the progress of their vessels and adjust for any delays.